Sorry, this site has been hacked. A new website will appear shortly.

Archives 2010-2011

Posted: May 1, 2017 in UncategorizedInternational-Women’s-Day-2017–International-Women’s-Day-2017–

The Century of Women

.

.

This year’s International Women’s day is different from so many I have celebrated since the 1970s. Millions of women have been active and on the march over the past few months. You don’t have to give it a name to recognise it’s a movement. Women’s anger and women’s power are issues for the whole world now.

We can’t be content with just one day of international protest and action. Not even a year will be enough for everything we need to do to win equality and freedom for women. Let’s go for the whole century. Let the 21st century be the century of women.

To do that we have to start now and we should try to include everybody who wants to change the lives of women and girls and those of men and boys in the world we will shape together.

Here’s a poem for this special International Women’s Day.

The pictures below are from my childhood in South Africa. Even then I can remember refusing to do what girls are supposed to.

.

Poem for a newborn girl on International Women’s Day 2017

for Masha who is very new

and for Moon who is already asking why

Welcome to the world of limited opportunities.

it is yours to make your own.

.

From child to woman

is a wondrous transformation.

Chance is always possible.

.

Grasp this world in your hands

as you grasp the first finger

feel it take shape

as you mould it to your will

your world, a girl’s world

.

Gulp its freshest air

to swell your open lungs

you’ll need them later

to shout your demands

a girl to be heard

.

Kick away the barriers

with your agile heels and toes

run far enough, climb high above

no one can stop

a girl who won’t be caught

.

Open your eyes

beyond history & tradition

you can see the path

you can choose to follow

a girl who wants to learn

.

Welcome to the world of unequal distribution

let’s tip the scales together

when you’re ready to decide.

.

A thinking woman’s life

is a voyage of resistance. Still.

.

© Karen Margolis

March 2017

.

Posted 7 March 2017

.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

JORGESEMPRÚNJORGESEMPRÚNJORGESEMPRÚNJORGESEMPRÚN

He remained uncompromising, even in old age. “If I were 20 years old again, I wouldn’t think twice about the Communist revolution,” he told the Spanish paper El Periódico. “I would set up a blog in Internet and spread inflammatory ideas.”

HOMAGE TO JORGE SEMPRÚN

the great Spanish writer who fought Franco’s fascism in Spain and Nazi fascism as a French Resistance member, and survived Buchenwald concentration camp.

He died in Paris aged 87 on 7 June 2011.

Back to Buchenwald

in honour of Jorge Semprún

When in the dawning light I turn the radio on

Smooth voices tell me of the crimes of former years

Each day begins with suffering that’s never gone

The evening shadows harbour numbrous fears.

A people’s eyes are turned toward the past

Their evil deeds are thrown back in their faces

Fate has entrapped them in an iron cast

The blood of millions keeps them in their places.

Today the victims speak their tragic stories

Another Sunday full of incantation

A nation bends its knee and grimly glories

In swamps of guilt and self-recrimination.

Once there was a beechwood, they took its name in vain

Besmirched its tree trunks with bad blood. It can happen again.

Once there was a beechwood, so proud in sun and rain

Why don’t they give it back to nature? Let silence heal the pain.

© Karen Margolis 2011

This poem was written in April 1995 as part of the poetry cycle “The Ballad of the Wrapped Reichstag”.

Jorge Semprún (10 December 1923-7 June 2011)

Photos from Wörlitz National Park

(UNESCO world heritage site), Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, 31 May 2011

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

MRS. COURAGE IN BERLIN

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch reads from her memoirs in the Zionskirche, Berlin 26 May 2011

1. Overture: Bomb chaos

The event begins with a bomb. On the afternoon of 26 May, Berlin local radio announces that

a 250-kg British aerial bomb from the Second World War has been found near the

Oberbaumbrücke between the city districts of Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain. It used to be the

bridge where pensioners from East Germany were allowed to cross the Berlin Wall border to

visit their families. Recently it has become a place for scene parties and art happenings. And

today, a bomb site.

All through the afternoon police are busy closing roads and evacuating thousands of residents

living along the River Spree. Buses and subway trains stop running in the area. Experts from

the Berlin state police force are preparing to defuse the bomb at May-Ayim-Ufer. A few years

ago this street along the riverbank was renamed in memory of May Ayim, a Ghanaian-

German writer and poetess who committed suicide at the age of 36 in 1996. An outspoken

anti-racism campaigner, she was renowned for her pioneering work on racism and skin

colour, and fiercely criticized by conservative academics.

The historical event of the day hasn’t even begun and already we are wrapped in layer upon

layer of circumstance, an agglomeration of periods and places because the city doesn’t just

breathe and move, it continually emanates threads that weave the past into the present in an

invisible fabric that swaddles every facet of daily life.

The bomb from a British fighter plane buried in the ground for almost 70 years under a street

whose name changed how many times on a political whim was discovered on the day of Anita

Lasker-Wallfisch’s reading in Berlin. At the time the bomb was dropped, Anita Lasker-

Wallfisch was a prisoner of the Nazis, stripped of her German citizenship and

all her worldly possessions because she was Jewish. She returned to Berlin in May 2011 at the

age of 88 as a British citizen. A survivor who escaped the hell of Auschwitz and Bergen-

Belsen and came back to show the power of resistance. By just being there, in the centre of

Berlin, she was defying the spirits of destruction that caused the Holocaust. She was a living

celebration of the survival of the Jews and all the other victims of Nazi racism and

warmongering. As a purveyor of memory she was the human counterpart to the bomb that

stopped the traffic that day.

2. The Setting: Zionskirche – the Church of Zion

It is a cool, windy May evening. Blowy enough to play havoc with the hair of the people

waiting patiently in line at the church door for tickets — but most of them have little hair left

to wave in the wind. The audience is distinctly elderly, as on so many similar occasions.

Many of the people are familiar from Jewish Community and civil rights events. Two active

social groups overlap here: those concerned with Nazi fascism and its aftermath and those

interested in the history and effects of 40 years of communist rule in East Germany. Together,

they make up the regular local clientele for Berlin’s much-cited “culture of remembrance”.

Here in Zionskirche we are reminded once again that it’s just as much a culture of forgetting.

The church looks rundown and dusty. A good example of 19th-century Lutheran church

architecture, built by Kaiser Wilhelm I to raise the tone of the surrounding working-class

urban district, it has no elaborate stained glass windows with Biblical figures and scenes. The

tall windows around and behind the altar are filled with small diamond panes in yellow and

orange. The evening sun shines through like a blessing. The only thing that disturbs this

pleasant shabbiness is a huge bright cross made of heavy cloth hanging over the altar table.

It’s like a patchwork of primary colours, with a large red spot on one side of the horizontal bar

and the words, “Ich habe keine Angst” (“I am not afraid”) stitched across a blue and green

wedge on the other side. This primitive, aggressive modernism makes the peeling splendour

of the surrounding walls and gallery look almost elegant, like a faded Hollywood star from

the silent movie era.

Zionskirche feels like a poor relation in the city’s ecclesiastical family. A leaflet on the

entrance literature table titled “Zion – building site”, appeals for donations for urgent

restoration. “Zion needs refurbished windows, toilets and more heating.” By the end of the

evening our cold toes are saying amen to the heating plea. And we have heard an impassioned

speech by historian Michael Wolffsohn, a leading expert on 20th-century Germany and the

Nazi period, reminding us that this was a church of resistance. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, one of the

key figures in the Church resistance against Nazism, worked here in the early 1930s. Under

East German communism the church became famous as a centre for punks and other young

dropouts and outcasts. Rock concerts and alternative happenings were held on the premises,

and it was even the target of an attack by East Berlin neo-fascist skinheads. Like most East

German churches, it was left to decay by a state that wished religion would disappear in the

process of communist evolution.

“Memorial centres and sites commemorating the perpetrators are all well and good,”

Wolffsohn said. “But we should make a special effort to keep the memory of resistance alive

in places like this church.”

Still, I’m running ahead. Michael Wolffsohn said this after Anita Lasker-Wallfisch had read

from her memoirs. He had to talk about the future because after she told us her story there

was nothing anybody there could add about the past. The voice of a survivor telling her story

is unique.

3. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch reads.

She needs no introduction, and mercifully there is none aside from a brief greeting. She

begins reading without any preamble. A low, well-moderated voice tells a story of loss,

torture, destruction and extermination in a measured tone that precludes any false emotion. As

she reads, her head with its thick covering of short white hair radiates quiet pride and dignity.

Here she is, in the middle of Berlin, not far from the headquarters of the Nazi terror machine,

and she tells us she has conquered an inner refusal to come here and feels proud of that

conquest. She comes as a survivor who made a new life in another country. “The rupture

between my first and second life was too radical,” she says. She comes here from her

“second” life as a British citizen, a mother and grandmother, and yet there is so much that still

connects her to that first life as a child in a Jewish family in Breslau, now Wroclaw, in the

former German Reich.

Her family wasn’t very Jewish, she says. Later she regretted that her parents hadn’t taught her

something of Jewish tradition that she could pass on to her own children and grandchildren.

But why should they? They were assimilated, and proud to be German. Her father was

especially proud of his Iron Cross won in combat in the First World War. He and so many

other Jews. Not that it helped. Later, after all the racist laws and decrees and being forced to

hand in radios and bicycles, and seeing the wilful destruction of the Reichskristallnacht when

the streets around Jewish shops and businesses were covered in blood and glass shards, later,

after all that, and after all the futile attempts to get exit permits and visas for safe countries,

her father realized there would be no return. On the night before Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s

parents were due to be deported, her father called her to his study and told her that at 16, she

was old enough to look after herself and her younger sister, Renate. True to his German

training, he had carefully prepared all the accounts for the time after his departure. “This is for

the rent and the gas bills…” The following morning the parents left for the assembly point.

The two daughters never saw them again.

Though Jewish education may have been lacking, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch is grateful to her

parents, and especially her father, for educating her in the best German tradition. After her

reading, Michael Wolffsohn complimented her on her beautiful written German, her ability to

tell a story clearly and accurately. The word he used was “Bildungsbürgertum”, the classical

tradition of German education that emphasized hard work and the disciplines of the

humanities but also prized poetry, prose and music as great achievements. Anita Lasker-

Wallfisch thanks her father to this day that he made his daughters speak French every Sunday

— although she found it tiresome at the time. The twists of fate that decide between life and

death made it possible for her to put that French to good use in forging identity papers in

Nazi-occupied France, just one of the stations in her odyssey to the death camps.

In December 1943 she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. “Incredible,” she exclaims. “They

actually made me sign a document saying I was going to Auschwitz voluntarily!” (Of course

“they” — the Gestapo — did. Then they could claim she had abandoned her property so they

could impound it. The Nazis robbed the Jews of millions with tricks like that.) In Auschwitz,

once again, she had reason to be grateful to her parents for that excellent education. She

remained alive in the death camp because she could play the cello. A fellow prisoner, Alma Maria Rose, niece of

the composer Gustav Mahler, told her, “You will be saved.” She was picked to play in the

“girls’ ensemble” that accompanied the prisoners going to and from work in the

camp.

“Black figures, baying hounds, the terrible stench…” – those were her first — indelible —

impressions of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Finally, after more attempted escapes and a proliferating scenery of carnage as the Allies

advanced, she was reunited with her sister and they arrived among the mountains of corpses

in Bergen-Belsen. Nearing the end of her terrible story, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s voice

quivers only slightly as she describes being ordered by the Gestapo to drag piles of bodies

towards the crematorium, and being too weak to obey. Even after they realized the guards had

abandoned the camp, she and her sister sat exhausted, propped up against the wall of a prison

hut. Suddenly she heard a loud voice over a megaphone (I quote from memory):

“THIS IS THE BRITISH ARMY. WE HAVE COME TO LIBERATE YOU. DO NOT

MOVE. THERE IS NOTHING TO BE AFRAID OF.”

I have been weeping pretty much nonstop for the past half-hour of this reading. Since Anita

Lasker-Wallfisch’s parents were deported, in fact. Suddenly I give my eyes a final dab and sit

up straight. I’m proud. Proud to be British. Proud to be a naturalized citizen of a country that

fought fascism at great cost and liberated the concentration camps with bravery and gave

shelter to many victims of the Nazis and their families. A country that integrated refugees and

victims of political and racial persecution and made them feel proud to be British.

I only wish I could say the same about Britain today! — and Michael Wolfssohn, pointing to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s beautiful German prose that didn’t protect her from ostracism and attempted genocide, warned us to be wary of immigration policy in Germany as well.

Integration isn’t merely a question of language, it’s a way of being and feeling, of embracing while preserving difference and distance. .

4. Signing the books.

After Avitall, the cantor of Berlin’s Jewish community, has paid musical homage to Anita

Lasker-Wallfisch, saying how moved she was because many of her own family perished in

Auschwitz, the author shows her incredible stamina by signing scores of copies for eager

buyers of her book. She takes the trouble to talk to each of them. Especially the younger ones, who smile shyly in the presence of living history. The young man on the bookstall

is beaming. A model author. A woman with a mission endowed by life. An unforgettable personality.

5. Mrs. Courage and a heap of rubble.

The streets are clear, almost empty as we drive through the city centre. The bomb was defused

without further incident at 6.30 p.m. There are still plenty more buried under the city. Large

tracts of land in the city centre, the heartland of the bomber raids, remained waste ground or

no man’s land after the war and the building of the Berlin Wall. The excavations for the

massive redevelopment after the fall of the wall uncovered masses of unexploded bombs.

According to Berlin historian Laurenz Demps, “In the period from 1 January 1991 to 31

December 2007 the firefighters of the Explosive Ordinance Disposal Service defused and

salvaged a total of 7,819 bombs (including incendiary bombs) and 1,069,390 kg. of buried

explosives and war rubble. In April 2009 the newspapers reported, “3000 bombs still buried

in the ground”.* I’m reminded of Bertolt Brecht’s comment when he arrived back in Berlin in

1946 after exile from the Nazis. “Berlin? – that heap of rubble near Potsdam.”

Near Jannowitzbrücke, a bridge not far from the scene of the bomb, we drop off our friend

Simone who was with us at the reading. As she gets out of the car, she points towards the

looming the TV tower at Alexanderplatz, its facetted ball winking and blinking in the

floodlights. She has a clear view of it from her apartment window in a former communist

concrete slab block overlooking a huge expanse of wasteland. All of this — the renovated

East German tower blocks, the empty site with the rusty fence destined, no doubt, for a

glorious real estate future, the landmark TV tower, the rows of shiny new buildings along the

embankment, the lingering traces of the Cold War border, the undiscovered aerial bombs

buried under the streets… all of that and so much more in this city and its people is a direct

result of the brief period of Nazi rule that left its mark on the world indelibly, forever.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s reading in the Zionskirche

in Berlin is that she had the courage and greatness of heart to come here at all.

____________________________________

*Laurenz Demps, “Berlin and the Consequences of Nazi Tyranny”, Berlin 1933-45: Between

Propaganda and Terror, ed. Claudia Steur, Berlin 2010 (Engl. translation: Karen Margolis).

Coda:

The music to go with this article:

Ofra Haza: Kaddish

“For salvation – Kaddish

for redemption – Kaddish

for forgiveness – Kaddish

for health – Kaddish

for all the world’s victims – Kaddish

for all the Holocaust’s victims – Kaddish.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hQ0OkcLKuE

© Karen Margolis 29 May 2011

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

… sometimes it just doesn’t work out…

Stillborn Poem

for Ruth

Sat down to write a poem

a man came into the room

to use the telephone

the title flew out of the open door

a boy came into the room

to tell me why Russia is cold

the first line fell into an ice hole

a postwoman came up the stairs

to hand over a registered letter

the rhythm fled with her departing footsteps

my mobile rang twice

the display was blank

a harsh voice shattered my rhyme.

The poem came out unripe

shrivelled and aged before its time.

Grieving, I cut the cord

to my botched creation

and gasped for breathing space

until the next interruption.

© Karen Margolis 2008 / 2011

””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””’

Berlin – city of change

changing

change money

a prelude to spending

change a man

change tactics

make a list

minus side longer

draw an ultimatum line

impose a fine

change trains

change habits

hack away at them

they grow teeth — bite back

chop them off

they flourish all the more

like snakes on the gorgon’s head

pull them out at the roots

they multiply in the hand

change cigarette brand

change hairstyle

a prelude to hoping

change heads

change clothes

a prelude to dieting

change sizes

change shoes

a prelude to dancing

change feet

change drugs

a prelude to flying

change carpets

change homes

a prelude to moving

change routes

change work

a prelude to retiring

change partners

change places

a prelude to parting

change faces

change shops

a prelude to consuming

change products

change cases

a prelude to declining

change contents

change colour

a prelude to blending in

change scenery

ring the changes

a prelude to cashing in

change rings

change choices

a prelude to deciding

change free will

change dates

a prelude to lying

times change

change a man

do it fast

exchange rate falling

all the time

change money

do it fast

change gets smaller

all the time

the dime stores fuller

change change

© Karen Margolis 2011

Tempelhof Airport is the latest setting for change in Berlin. A few years ago flights still took off and landed here and passengers walked through the old halls, footsteps echoing in the original 1930s stone halls, with the feeling of occasional glimpses of 20th century history behind the square pillars and deco moulding. Tempelhof, the scene of some sinister and some heroic airborne missions, is now closed for flying and open for future speculation.

What to do with the world’s largest interconnected inner-city space? In the gap between temporary use licenses, urban planning resolutions and architectural competitions, the Berliners, adepts at improvising after a century of upheavals, have claimed the space as their own.

Watch this space. It’s the perfect venue for Berlin’s contribution to the international poetry event

100 Thousand Poets for Change

on 24 September 2011.

More later…

…meanwhile, here’s a look at Tempelhof Field over the Easter weekend:

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

…. heard something about a wedding? ….

Retro not Metro

The royal nuptials nostalgia show

The bride has been groomed

the groom has been briefed

they both passed the test

without coming to grief

from the dead princess’s hand

a symbolic ring

the world media rights are sold

the show can begin

They say family

it means patrician loyalty

they praise tradition and glory

it’s a nostalgia orgy

There’s gold stick-in-waiting

and silver stick, too

street liners, path liners

and licensed film crews

eight 20-foot-high trees

inside the old abbey

and a disinvited despot prince

for the sake of diplomacy

They say marriage

we see military

they say carriage

we hear cavalry

160 army horses

all along the route

eight hours of polishing

the infamous jackboots

swords, plumes, horse tack

helmets & cuirasses

1000 men-at-arms or more

and military musicians

Valiant and Brave

the trumpeters will play

a wing commander’s fanfare

composed for the big day

valiant and brave

the bride & groom must be

to get through this marathon

of pomp and ceremony

household guards, honour guards

Grenadiers, Blues & Royals

historical escort troops

for queen and bridal couple—

while to show they’re in touch

with folk of the nation

sports idols and popstars

will be at the reception

They say renaissance

we hear patriotism

they talk of values

we see militarism

The battle is on

for marketing and media

saturation bombing

with sentiment & trivia

In the master plan, after

the kiss on the balcony

two billion viewers

across the globe will see

the ghosts of the past

as vintage aircraft

the Battle of Britain

memorial flypast:

a Lancaster, a Spitfire,

a Hurricane, and then

two Typhoons & two Tornados

paired in box formation—

a royal air force in the sky

of oldtimer jets

under the enduring motto

LEST WE FORGET—

union and reunion

for an heir to the throne

a fitting initiation to

the connubial combat zone

© Karen Margolis April 2011

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

There’s a jar of gefilte fish (Hungarian-style) in the cupboard waiting with the matze boxes (family pack). Passover is on the way. This year in Berlin, next year in Jerusalem. Maybe. The preparations awaken thoughts of Pesachs long ago.

Matzes v. Trotsky

On a homeopathic cure for residual religious and political ailments, our narrator Karen tries a dose of Passover at a festive dinner in Berlin — and breaks out in a memory rash.

By the time we arrive at Middenweg, most of the guests are already seated. The synagogue has been transformed into a noisy banqueting room with two parallel tables along the length of the hall. At the centre of the head table running across the top are the rabbi and his wife, flanked by the synagogue elders and their families. The glamorous young woman sitting next to the rabbi is Ronia the cantor, wearing an embroidered prayer shawl and a decorative pillbox cap on her luxuriant blonde curls; a feminised oriental version of the ceremonial garb. We find two empty seats at the bottom end of the table near the kitchen. The rabbi’s wife waves to us. The treasurer, a small man with greying moustache, comes over to collect the dinner money. There are already around 60 people here, with more arriving all the time. The TV crew that recorded Purim is here as well, with the lady producer also in oriental style in a long glittery dress and extravagant earrings. A tall dark photographer with an enviable Nikon is hovering discreetly; he looks professional. Everybody’s talking except the boy next to me, who’s got that bored-and-scornful teenage look I remember so well: “I wouldn’t be here at all if my parents hadn’t dragged me along. Can’t wait till next year when they won’t be able to stop me going to the disco instead.”

If I were he, I wouldn’t be here either. Teenagers usually want to be among their peers. This seder company has a smattering of small children, but most of the guests look like grandparents. The chair waiting for the prophet Elijah isn’t the only empty space. There’s a big gap where the teens and twens should be; and the few 30-somethings are mostly married couples with young kids accompanying the grandparents.

The homeopathic Pesach dose is stronger than I anticipated and has instant effect. My mind goes into split screen. One part is watching the scene around me, showing Thomas the picture in the Haggadah that identifies the symbolic bits and pieces on the plate in front of each guest. This is the first time I have ever brought a non-Jew to a seder and I realise how mysterious it must seem to the uninitiated. The glaring neon lighting in the room doesn’t help; it makes the items on our plates look limp and grey compared to the bright colours in the book.

The other half of me is on fast rewind, spooling back, back, back to the last seder 25 years ago at my parents’ house in Hampstead. Every springtime after my twin sister and I left home, my mother would phone up in advance to make sure we were coming to the seder. Our Spanish flatmate Rosita, who had her own share of family duties, dubbed Passover “your Christmas dinner”.

At the age of 24 I decide to duck the roll call. When my mother phones, I tell her that on seder night there’s an important meeting of my political group, the International Marxists.

“But nothing can be more important than the family,” my mother says.

“Well, this is,” I reply firmly. “There’s a crucial vote and I have to be there.”

“Why don’t you ask for a postal vote?” my mother says with sweet reason. “I’m sure they’ll understand if you tell them it’s Pesach.”

“They won’t. Trotskyists don’t believe in all that,” I answer impatiently. “You know what Karl Marx said: religion is the opium of the masses…”

I realise my mistake as soon as I’ve said it. The mention of Marx brings out all my mother’s wrath. “That man Marx said a lot of stupid things. Just look at Russia. How they persecute the poor Jews behind the Iron Curtain.”

Now I’m hopelessly entangled. “You can’t blame it all on Marx,” I argue. “It was Stalin who betrayed the revolution — ”

“— I wasn’t asking for a history lesson,” my mother interrupts. “I only phoned up to tell you that your place will be set at the seder like it is every year. Just because you lead a bohemian revolutionary life doesn’t mean you can turn your back on the family.

“And anyway — “, she pauses for the parting shot, “— your brother is looking forward to seeing you. He’s built a kind of computer he wants to show you.”

My mother knows my weak spot. I can resist anything but my younger brother. He was born when I was 11, and I can clearly remember the day when my aunt fetched my sisters and me from school with the news. We took the 24 bus from Hampstead to University College Hospital in Bloomsbury, and saw a greasy wriggling little bundle through a glass window. Perhaps it was his naked ugly perfection that made me love him wholly and unconditionally from that first moment. I can remember whispering a soothing song to comfort him eight days later for the little gauze bandage on his penis after the circumcision (to which his sisters were not invited). Friends and family arrived to admire him, commenting: “At last the family is complete.”

We three sisters looked at each other, astonished. We hadn’t realised we were incomplete.

Sitting at the seder table in March 2002 is not the time to start meditating on the irrevocable harm caused by learning at a tender age in a past century that your sex is the wrong one. I’ll only say that the hurt I had long thought healed resurfaced another springtime in Berlin almost twenty years later when I wrote the bitterness and anger into a poem.

Family History

Mother tied my hands behind my back

with the umbilical cord

Father beat me with the stick of conformity

Long-suffering sisters stuck pins of jealousy

into the moulded picture of me.

Baby brother took a long time to arrive.

Great rejoicing. A manchild:

Now, they say, the family’s complete.

On the eighth day

initiation rites

secured his place within the tribe

(His sisters were not invited)

He had a godly property

that won my mother heart and soul

I only a hole

the emptiness

I try to fill with love.

Still, life’s getting easier

since I stopped looking for my good parents.

Berlin, April 1995

I never held a grudge against my little brother. At his bar mitzvah in 1977 shortly before that last seder, I was every bit the proud older sister. (Though I did manage to annoy my elders by wearing a big Women’s Liberation badge to ward off the patriarchal spirits in the synagogue, and pointedly asked Reverend Bronsky how long it would be before girls were allowed the privilege of a bat mitzvah under his conservative ministry.)

When my brother was still in his infancy I taught him Beatles songs and his first mathematics and chess. Now he’s a computer prodigy. I don’t see enough of him. I can’t disappoint him by not coming to the seder.

At the next International Marxist meeting I tell my comrades that I won’t be at the crucial debate the following week. The chairman demands the reason. Passover, I say. I have to go to the family celebration.

“That’s not a valid reason,” he says.

“It’s the only one I’ve got,” I reply. (Stifling the impulse to fish for sympathy by invoking my little brother.)

Silence falls over the smoky back room of the pub. From the saloon bar next door you can hear the sound of billiard balls colliding, and the satisfying rattle as they fall into the side pockets of the table. There are at least three other Jewish people at the meeting. They avoid my gaze.

“Do you mean to say,” the chairman asks slowly and deliberately, “that you’re going to let your family dictate to you with their ancient superstitions?”

The sneer in his voice with its carefully cultivated Irish brogue rouses me to anger. It flashes through my mind that I could call him an ignorant Guinness addict. What dogmas did he imbibe with his mammy’s milk before he developed his taste for the harder stuff? He’s also got a weakness for IRA-style bomber fantasies. Unconditional but critical solidarity, he calls it.

This is what happens when people insult me for being Jewish: I want to hit back. A gut reaction. I’m hurt that he’s questioning my revolutionary credentials just because I can’t deny my family.

All this in the split second while I’m listening to the chairman asking the others for their opinion. Nobody knows what to say. They’re embarrassed at this religious family stuff intruding on the agenda. The chairman is proposing a vote.

“Hang on,” I say. “You can’t seriously mean you’re going to vote on whether I can go to my family for Passover? — that’s a personal decision, not a political issue. I did you the courtesy of telling you I wouldn’t be here. But I’m going anyway — whatever you decide.”

“Don’t interrupt in the middle of a vote,” the chairman snaps. “Now: hands up all those in favour of Karen having leave of absence for her… ”

He pauses to pick his words, and blurts out awkwardly: “… for her family religious do.”

I get up and walk out of the room without looking back.

Afterwards I heard that the twenty-odd comrades at the meeting voted two to one in favour of my being allowed to miss the crucial meeting for Pesach. Some of my supporters kindly advised me to reconsider my priorities. The rest never mentioned the incident again; but from then on I knew I was regarded as a weak link.

That last seder 25 years ago was the moment I finally cast off the fetters of Judaism. It was also the beginning of my drift away from the Trotskyist movement. A passionate, overwhelming desire for personal freedom eventually led to my renouncing creeds and parties. They seemed to be run mainly by men and to demand exclusive loyalty. I wanted to be a free citizen of the world, not a prisoner of a family, a party, a sect or a particular nation. Let alone a prisoner of my sex.

The following year, I left the International Marxists. In my resignation letter I didn’t mention the pre-Passover meeting in the pub, but it obviously still rankled. I accused the group of being like a 19th-century school where authoritarian masters whipped the pupils into line with a principle called democratic centralism: top-heavy on centralism and ultra-light on democracy.

Since then I have been wary of organisations of any kind, political or religious. I finally tossed the legacy of patriarchy into the dustbin of history and stopped being a good girl.

© Karen Margolis 2008 / 2011

Excerpt from Chapter One of A Renegade Jewess

Welcome to my 21st century sweatshop

Posted: April 21, 2015 in UncategorizedTags: civil liberty, feminism, identity, passion, poetry, selfie, sexy at sixty, surveillance, transparency

*heroines.and.anniversaries*heroines.and.anniversaries*heroines.and.anniversaries*

History in the Margins

.

.

Ravensbrück concentration camp: 70 years after liberation

If you’re looking for heroines – real women who performed deeds of great daring and bravery – Ravensbrück Memorial is a good place to go. It stands on the site of Ravensbrück concentration camp, the only camp the Nazis set up exclusively for women. The surrounding landscape of Brandenburg in northeastern Germany close to the Polish border is flat and empty, an expanse of woods interspersed with beautiful lakes. Berlin is only 50 miles to the south, but a world away.

British journalist Sarah Helm was looking for heroines when she first discovered the story of Ravensbrück camp. She was researching for a biography about Vera Atkins, an officer in the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), the British military intelligence network that fought secretly against the Nazis in the Second World War. The SOE parachuted many women agents into Nazi-occupied France where they worked with the Résistance, often as radio operators and couriers. Although Atkins never worked actively in the field, she was the commanding officer of a number of SOE agents who operated in France and were later arrested and deported to Nazi concentration camps. Among those agents, Denise Bloch, Lilian Rolfe and Violette Szabo were executed at Ravensbrück on 5 February 1945 and Cecily Lefort was murdered in the gas chamber at Uckermark Youth Camp close to Ravensbrück sometime in that month as well.

.

Author Sarah Helm (standing) speaking about her book at the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Ravensbrück, 19 April 2015

.

A barn in Vera Atkins’ garden in southwest England housed the archive of her wartime intelligence work. There, Sarah Helm learned with shock and disbelief about Ravensbrück, one of the greatest crimes ever committed collectively against women. Slave labour, horrific medical experiments, murder of newborn babes, forced prostitution, the cruelty of women guards to women prisoners … from 1939 to 1945 this was hell on earth for more than 130,000 women and children, 20,000 men and 1,000 teenage girls and young women. 40 subcamps made up a network for slave labour that spread right across the region and beyond.

.

Women prisoners “shamed by humiliation”

By the time Sarah Helm read these stories, more than 50 years had already passed. She was amazed she knew so little about Ravensbrück. Why was there such ignorance about it? The more she met and talked to survivors of the camp, the more she realised how many had kept quiet. “Women felt particularly shamed by the humiliation they suffered from the Nazis,” she said. French survivors told her the first question they often faced when they returned home after liberation was, ‘Were you raped?’ Although the answer was usually ‘No’, the women felt their experiences in Nazi captivity had made them victims of collective violation.

In an interview several years ago, Yvonne Baseden, a former SOE agent who survived Ravensbrück, urged Sarah Helm not to write the story of the camp for women. “You have two young daughters,” she said. “Perhaps it is just too horrible for them.” But Sarah Helm wasn’t just interested in rescuing Ravensbrück from its obscurity “stubbornly in the margins of history”. She wanted to discover what made a women’s camp different. She went on to write her recently published book, If This is a Woman, the biography of the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück. The title refers to Primo Levi’s masterpiece, If This is a Man, one of the greatest works of literature by a Holocaust survivor.

Inhumanity and slave labour

.

Ravensbrück’s network of satellite camps and work details for slave labour (from permanent exhibition)

.

At the ceremony on 19 April 2015 to mark the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the prisoners of Ravensbrück, Sarah Helm stood on the stage on the former assembly ground and pointed over the heads of the crowds of guests and spectators to the treetops beyond. The chief guard of Ravensbrück, Dorothea Binz, was a simple woman, Helm said, a forester’s daughter who came from those woods just over there. What made her into a monster of legendary cruelty who tortured and murdered women, men and children in her charge? Why were so few of the camp guards prosecuted or sentenced after the war? Why, above all, were many of the slave labour bosses never been called to account? Helm particularly mentioned the thousands of women did slave labour at Ravensbrück external camps for Siemens (and Mercedes Benz, I might add). – Why have those women never been adequately compensated while the companies profited hugely from their toil? Many of them literally worked to death. Shame on Siemens, said Sarah Helm, speaking loudly enough for Germany’s industry bosses and politicians to hear. Even after the thorough cleansing and reparations of the past 70 years there are still some pockets of injustice left to sew up in today’s new Germany.

.

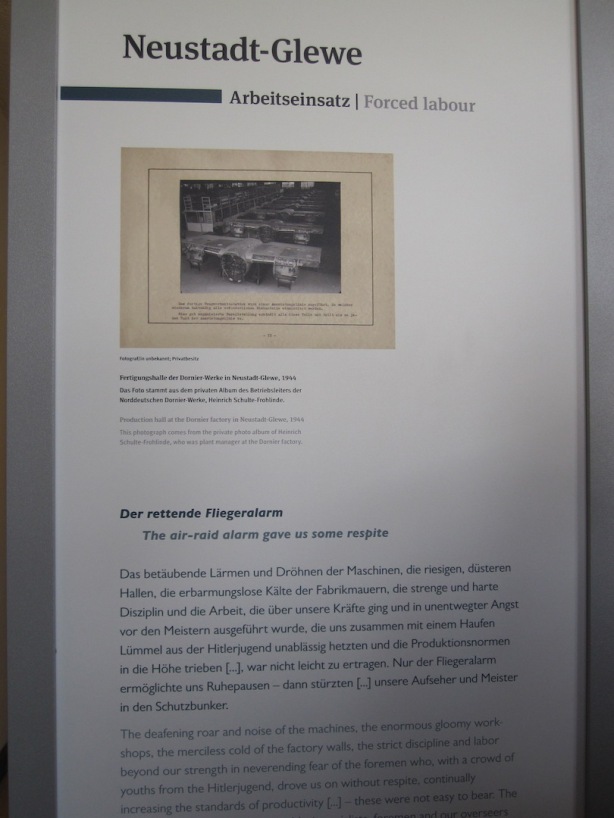

Slave labour in the aircraft industry at Neustadt-Glewe work detail. Working conditions were arduous and many prisoners died on the job.

.

But Sarah Helm wasn’t merely interested in exposing inhumanity or redressing the victims. She wanted to pay tribute to all the brave women who defied the Nazis and helped each other and remained human despite everything. She singled out Elsa King, the prostitute from Düsseldorf who was renowned for her courage and kindness and was gassed in the Nazis’ ‘euthanasia’ programme in Bernberg. Or the women who wrote letters using their urine as invisible ink to try and publicise their plight and the crimes in the camp. Or the doctors who saved patients in many ingenious and risky ways. She pleaded, too, for us not to forget the Communist women who remained faithful to their country and cause all through the Nazi captivity, only to be arrested and persecuted back in Stalin’s Soviet Union for having been caught by the enemy. Not forgetting the brave Polish women who resisted German occupation in Warsaw and fought in the uprising that was so brutally crushed by the Nazis in 1944. Many of those women were sent straight to Ravensbrück on arrest.

And what about the Jewish women who had often lost all their family and had been through an odyssey in the various camps of the Nazi Reich? – as part of the group that suffered the most from the Nazis, they have a well developed structure to defend and preserve their memory. Mindful of what it means for the dwindling number of remaining survivors, the Israeli delegation to Ravensbrück this year was particularly large and accompanied by many young assistants and volunteers. Polish and Ukrainian visitors stood out as well. The grounds of the former camp were vividly populated by several groups of nuns wearing embroidered Polish emblems and carrying their national flag on their way to wreath laying at the wall of remembrance. There was an air of class reunions, of a big day carefully planned ahead in the lives of each visitor old enough to remember what this assembly ground looked like when the SS held the roll call in the early mornings that always seemed to cold or too hot, while the women guards cracked whips, waved truncheons and held their vicious dogs on the leash.

.

.

.

.

But what of the unsung sufferers, the German women and men labeled ‘asocial’ and sent to Ravensbrück just because they were poor or defiant or wouldn’t conform to fascist ideas? They have been erased from history, says Sarah Helm – they don’t even have the status of victims.

.

The joy of liberation

Ravensbrück was the capital of the crimes against women just as Auschwitz was the capital of the crimes against the Jews. Sarah Helm believes we have much to learn from this unique camp, and is encouraged by the interest in her book especially among the younger generation. Perhaps the story is indeed too terrible to be told, she says. But it’s still worth telling. In the end it shows the triumph over death and evil.

After liberation, the Red Cross took some of the women to Sweden. Sarah Helm quotes the astonished reaction of diplomat George Clutton who welcomed the survivors in Malmö. He had never seen seen people so full of the joy of life. Now that’s a story worth telling, over and again.

.

.

Heroines – Secret Agents

One of the most terrible sights at Ravensbrück memorial is the ‘execution corridor’, a passage between two buildings where the condemned women prisoners were forced to walk through and were shot from the back. Three women SOE agents and several radio operators from the French Résistance were executed here. Accounts by other prisoners testify to their extreme bravery in the face of death. They are still revered and remembered today in the UK and in France.

.

.

Heroines – survivors – eyewitnesses

It’s hard to imagine the courage it takes to come back to the place of pain and talk to the descendants of mass murderers and try to spread the word that each human life is precious and fascism must never happen again… The remaining eyewitnesses of the Nazi atrocities bear precious testimony, and the media crowded around to hear their stories.

.

.

Heroines – A Plaque for Milena Jesenská

The Czech Ravensbrück Committee was responsible for one of the most touching moments of the liberation anniversary day. It sponsored a plaque for the Czech journalist Milena Jesenská who is known to the world as the woman immortalised in Franz Kafka’s Letters to Milena. After her relationship with Kafka she became a prominent left wing political journalist and later wrote on issues important for women. Sent to Ravensbrück as a political prisoner, she was welcomed into the elite Block 1 and much loved and respected by many other prisoners. Doctors in the infirmary fought hard to save her life but she died of kidney failure in Ravensbrück in May 1944, aged 48.

.

.

“She was a mediator between the Czech, Jewish and German spheres. She helped victims of persecution to escape into exile. After being detained in Prague and Dresden she was deported to Ravensbrück in October 1940, where she perished in May 1944.

She was one of over 2,200 Czech women imprisoned in Ravensbrück.”

.

It felt good to throw flowers into the lake. It has become a tradition on memorial days at Ravensbrück.

.

.

My small tribute to all the Hungarian victims and prisoners at Ravensbrück – the picture shows the Hungarian section of the Wall of Nations.

.

Text and pictures © Karen Margolis 2015

.

.

Worth reading: Sarah Helm, If This Is A Woman, New York: Little, Brown, 2015

This is dedicated to my friend Edita from Bratislava who lost her parents and sister in Auschwitz, was imprisoned as a young girl in Ravensbrück and worked as a slave labourer making aircraft parts in the Mercedes-Benz work detail in Genshagen, south of Berlin. Despite a long campaign, she and the other women labourers there, many of them from Hungary, have never received compensation. Edita was liberated by American soldiers and later fed and helped by Red Army soldiers to return home.

Posted 20 April 2015

###########################################

::berlin’s.a.cabaret.my.friend.::berlin’s.a.cabaret.my.friend.::

In Berlin. This haiku does not directly mention the weather.

.

.

Berlin mood haiku (spring version)

City in waiting

Always after and before

Never in the now

.

.

.

.

.

Poem & pictures @ Karen Margolis 2015

Posted 29 March 2015

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

.

##heads’n’scarves#heads’n’scarves#heads’n’scarves##

It’s not what’s on your head, it’s what in it that counts

.

.

Headscarves are in the news again this week in Germany. The Constitutional Court just overturned a previous ruling banning teachers from wearing headscarves in school. Specifically, this relates to headscarves worn by Muslim women for religious reasons. Depending on how you look at it, the lifting of the ban has been hailed as a victory for freedom of religious expression or an abandonment of the principle of keeping religion out of state institutions. It’s actually amazing how a relatively minor issue compared with the miserable state of much of the world has received so much media commentary. The headscarf issue has become invested with an enormous symbolism. Why?

.

.

Ideology of style

In an age where you are how you look, not least in the lens of your own mobile phone, outward appearance has become a statement with ideological impact. You assert your individualism against mass consumption by managing to look different at the same time as conforming . This acrobatic trick allows you to claim freedom of choice while slavishly following the dictates of fashion, religion, and private and public power relations. The discussion on the headscarf issue in the German press is laden with so many contradictions and weird cultural assumptions that it’s suffocating under its own weight. First and foremost, it has been hailed as a victory for religious expression, although nobody has been able to find any binding requirement on Muslim women to wear head covering. But the media are full of Muslim women telling us how relieved they are to be able to show their piety without censure, and if it makes them feel good I certainly have no objection. However, the argumentation that society as a whole will benefit from this decision is rather shaky. It’s hard to argue that general acceptance of dress codes for women is a step forward. But if Muslim women feel more confident in public when headscarves are permitted, so be it.

The main reason why it was necessary to lift the ban is that it was based on totally false assumptions. Germany, in common with most European countries, is not a paradise of laicity threatened by Muslim religiosity. On the contrary, most European countries are still deeply Christian in many respects, so deeply that we hardly notice how embedded Christianity is in daily life and especially in the calendar, from the day of rest to the major public holidays. As long as the Christian cross and pictures of Jesus or the Virgin Mary adorn walls in German classrooms (and they are still there in many places, particularly in the more Catholic south of Germany), there can be no talk of laicity and no ban on public display of any other religious garb or insignia. So it’s only fair to let headscarved Muslim teachers into the classroom, and Jewish men with kipas, Buddhist monks with their special hairdos, Sikhs with turbans etc.

On a practical level, head covering is unlikely to interfere with teaching. The burqah and other extreme forms of clothing, especially ones that prevent children seeing the teachers’ face, obviously pose much greater tolerance problems. The headscarf, in fact, is a borderline case that has become mainstream. It embodies a successful product unity of style and ideology in modern societies.

.

.

A feminist triumph?

The revised headscarf ruling has been welcomed generally by religious leaders of most faiths because they see it as strengthening the role of religion in general. That’s not good news for atheists, who have a difficult and relatively unprotected legal position in comparison with the religious, and certainly a far less effective lobby. Sharp criticism has come from women with Muslim backgrounds who are trying to fight for more laicity and less religion for Muslim women. And from some organisations who work with young women trying to escape the strictures of traditional families including Islamic faith being used as a reason not to let girls join in social life, swimming lessons, etc. or to choose their own partners and generally join in the wider society. The headscarf ruling may strengthen the hand of conservative mullahs in Germany who want to control women’s bodies and minds. That’s a battle for women within Muslim communities, and I wish them luck.

The oddest argument I’ve seen so far is from a left-wing newspaper columnist who hailed the new headscarf ruling as a triumph for feminism. Why? – because the overturned ruling had discriminated against Muslimas who wanted to wear headscarves as teachers, whereas no law had objected to the luxuriant facial hair sported by many ultra-religious Muslim men. Once again, the columnist wrote, women had been the victims of ideological battles between Muslims and the state. The trouble is, ideology or not, beards are in vogue nowadays and it’s often hard to distinguish between young religious Muslims and fashionistos.

Religion can make even simple things seem terribly important. But who knows? – maybe the headscarf will see a revival as a fashion item and the whole issue will lose its loaded religious quality and fade into the insignificance it deserves.

.

.

Those of us who grew up in the West in the 1950s remember headscarves as a staple item of female outdoor wear, not to mention the war widows. My encounters with the headscarf are narrated in detail in a chapter of my book, A Renegade Jewess. It is reproduced below for the occasion of the revised headscarf ruling.

A Renegade Jewess Part 3 Ch. 1 © Karen Margolis 2015

A Renegade Jewess

PART THREE: A Feminist Jewess

Faith, Fashion and Choice

how odd of God

to choose the Jews

W.N. Ewer

Verse & Worse, Faber&Faber 1958, p. 256

The woman in the headscarf sat at the back of the ladies’ gallery, following the

service intently in the prayer book. From where she sat she could hardly see the

action below, but that didn’t seem to bother her. She scarcely looked up at all. Her

lips moved with the songs and prayers, her eyes fixed on the Hebrew words

before her. She never spoke to her neighbours in the gallery, and she frowned

when the chatter around her grew too loud. My sisters and I dubbed her ‘The

Mouse’ because she always wore grey or brown skirts and beige twin sets. No

jewellery, no make-up, no decoration of any kind, not even the hint of a smile

relieved the drab, solitary appearance of The Mouse. She first appeared in the

Hampstead synagogue one spring Saturday morning, and from then on she sat in

her back seat every Shabbat and holy day until she became a fixture.

The Mouse’s most remarkable feature was her headscarf. Most of the women in

the ladies’ gallery wore hats, and those hats were something special. A new hat

for the high holy days was a talking point from the time it was sought on shopping

expeditions to the moment it was unpacked from its hatbox, unwrapped from the

tissue paper and donned for its premiere outing. During the service the hat served

as a beacon for the men folk looking up at their women and children in the gallery;

the more elaborate and striking the headgear, the easier for husbands and sons

below to spot their family above. Most of all, the hat was a status symbol that

declared whether its wearer shopped at posh West End department stores or had

to make do with the local milliner.

The headscarf, on the other hand, was an everyday item for charwomen, school

dinner ladies, factory workers and housewives hiding their curlers. In the 1950s it

enjoyed a brief fashion heyday inspired by pictures of Hollywood glamour girls like

Marilyn Monroe at home on the ranch, but by the Sixties, when we sat in the

synagogue, it had been relegated back to its origins — as folk costume or

functional headwear for women workers. For us, The Mouse’s headscarf was not a

religious, but a class statement.

On social occasions when the congregation crowded into the back room for

Kiddush, or gathered under the hanging fruit when the roof was slid back to

transform the room into the sukkah for the harvest festival, The Mouse remained

on the fringes. If we passed her in the crowd, we would murmur polite greeting

before sweeping past to grab niblets and fish canapés from the trays doing the

rounds. She would nod silently in reply and lower her eyes. We never saw her

eating the snacks or speaking to anybody except Reverend Bronsky.

Our mother rebuked us for our rude comments on The Mouse. “She’s a convert,”

she explained. “You have to treat her with respect. It’s not easy being a convert.”

Pressed to explain, my mother elucidated some of the hurdles that had to be

jumped to join Us, the Chosen People. Aside from learning Hebrew, studying the

Torah and being able to learning about Jewish practices and traditions, you had to

keep a kosher kitchen. The rabbi would come to check up whether you were doing

it properly. As our mother had given up the time-consuming rituals of a kosher

kitchen when we moved to London, where we had no domestic help, she was

reluctant to elaborate on the topic. If the rabbi had dropped in to check on her

larder, aside from non-kosher food he would have found forbidden goodies like

tinned shellfish. Our mother had a ready and rational argument for that: the dietary

laws had evolved in ancient times to preserve food hygiene and health in the hot

Oriental climate, hence the emphasis on clean slaughter, purifying of foodstuffs

and hand washing. Muslims, who originated from the same region, kept the same

laws for similar reasons. But nowadays, with humane and hygienic slaughter

methods, and fridges and sterile packaging, the old laws were obsolete. From our

mother’s viewpoint, selectively ignoring them was a sign of modern Judaism.

While we were curious about The Mouse in her charwoman’s headscarf, keeping

her kitchen kosher-clean, salting and soaking the raw meat before cooking, and

separating the cutlery and crockery for meat and milk dishes, the theme of

conversion and religious law unsettled my mother. Her mother-in-law had objected

to her as a bride for my father because she couldn’t be trusted to keep a kosher

kitchen, the primary test for a prospective Jewish wife. As children my sisters and I

had observed our parents preparing nervously for visits from the paternal in-laws.

Everything had to be double-checked to ensure that my grandmother’s sharp eyes

didn’t uncover any transgressions, dietary or otherwise.

My paternal grandmother was practically the antithesis of the modern woman my

mother aspired to. Under her headscarf was a wig. According to Jewish custom in

Lithuania, where she grew up, the bride’s head was shaved on her wedding night,

and remained covered from the world for the rest of her days. The custom

persisted into the modern age in some parts of Eastern Europe.

Among the Jews of the shtetl, as in Islam, the woman’s headscarf was a hands-off

warning to any other man except her lawful husband. Its secondary function of

concealing a primary element of woman’s beauty, her hair, also served to keep

male predators at bay. The headscarf was part of ancient strictures on female

modesty: the Hebrew Bible contains injunctions to women not to display their

attractions too openly, and warns of dire punishment for those who

disobey. In this sense, The Mouse’s outfit was quite religiously correct.

My mother, who had a talent for fashion drawing and loved fine clothes, was proud

of her emancipated style and contemptuous of women who obeyed religious dress

codes. The Mouse didn’t fit into her world. But there were other reasons, not

merely aesthetic, for my mother’s distaste of conversion — reasons shared

discreetly by most of our Jewish circle. In the first place, we were born Jewish. We

were born into the Chosen People, and that was an act of God, not a matter of

choice. Although it was never said openly, our Judaism was defined in terms of

ethnicity and tradition, not religion. My parents never distinguished between

apostate and practising Jews: the line they drew was between those born as

Chosen People and those destined to a life outside the fold.

This was no matter for pride or self-satisfaction, because being Jewish meant

suffering. Being one of the Chosen meant carrying the burden of six million

corpses all through your life, and reproaching yourself for surviving and enjoying

life, and having to be eternally grateful to the God that spared you on a daily basis.

It meant being ever watchful, fearful that the Terrible Event would come to pass

again. It wasn’t easy being chosen without any choice in the matter. It was more

like a duty imposed by an external power, or a tribute exacted for privilege and

good fortune.

.

.

There was another reason why we viewed female converts with pity mingled with

contempt. As my mother explained, the final stage of conversion for both men and

women involves immersion in the mikveh, the ritual bath — a precursor of

Christian baptism rites. Orthodox women are required to visit the mikveh for

purification on many different occasions, especially after menstruation and giving

birth, and before their wedding. In some Orthodox communities the woman

convert is accompanied by the rabbi’s wife or other respected female community

members. (Nowadays the rabbi’s wife is often replaced by a woman attendant, the

mikveh lady.) When the convert enters the shallow pool, the attendant women

duck her head under water until she is completely immersed. (Modern variations

include dipping alone or using a shower to ensure that head and body are thoroughly soaked.

My mother found this orthodox ritual bath repellent. Many strands of Judaism today,

including the Reform movement in the USA, have renounced the mikveh as

irrelevant, obsolete or incompatible with modern religious practice. Others have

developed completely new functions and meaning for it. But in Orthodox

communities the mikveh is still so important that construction of a synagogue can’t

begin before this ritual bath has been built, usually in the basement. Modern

mikvehs look like spa immersion pools, more sanitary than sacral, but the

ceremony is still reminiscent of biblical times. Much has been written about mikveh

rituals; some novels and memoirs by modern Israeli women testify to humiliation

and degradation suffered by women forced to go to the mikveh.

To many people in my parents’ generation who grew up immediately after the

Second World War and the Holocaust, being Jewish meant defiant rejection of the

persecution that had nearly wiped out their people. As young adults, my parents

embraced Zionism and dreamed of joining the kibbutz pioneers to build a new

society in Palestine. Many of their contemporaries took this path, often inspired by

socialist dreams. Young Jews rebelled against their parents and discarded ancient

customs and rites. They felt that no kind of piety or adherence to religious ritual

could have saved their murdered relatives from extermination. The image of a line

of Jews walking toward the gas chambers murmuring the shema in chorus was

ingrained in their consciousness: hardly an encouraging picture for the Jewish

youth of the future. Whether fighting for and building a new society in Israel, or

facing the consequences of adjustment to the post-Holocaust world in the

Diaspora — including emigration and adaptation to unfamiliar host societies —

many young Ashkenazi Jews of that period did not want to be weighed down by

the past. The ghettos of Eastern Europe that had housed their forefathers were

associated with the memory of Nazi ghettos and concentration camps of the

immediate past. The further my parents departed from this, the more they could

hope to ward off the shadow of extermination. Assimilation promised the benefits

of security in anonymity.

Our emigration in the 1960s from South Africa to London, just as the city was

becoming the swinging hub of the western world, intensified my parents’ dilemmas

over their Jewish heritage. However hard they tried to hang on to familiar patterns

based on religion and the family, their budding teenage daughters strained against

tradition and dragged them forcibly into the world outside. On Saturday mornings,

girls in miniskirts and boys with long hair strolled past the synagogue in noisy,

confident groups while we sat isolated in the service. Around us in the Ladies’

Gallery, women worshippers exchanged cosmetic and diet tips while the men

below keened and sang and swapped business gossip. We sisters sat there,

unwilling captives, searching for arguments to avoid synagogue. Religion was out.

.

.

Not for The Mouse: she obviously wanted in. Every Saturday morning she sat

frowning over her prayer book, a solitary reminder of a world other people had lost.

Why did she choose to join what we were struggling so hard to leave behind?

“Judaism,” Reverend Bronsky informed us at cheder, the Hebrew Sunday school,

“is not a religion of conversion.” My sisters and I exchanged glances, thinking of

The Mouse but unsure whether to broach the delicate subject. Converts had to be

respected, our parents said; but they also seemed to be despised, or at least

avoided. Reverend Bronsky confined his remarks on conversion to the present

day. He didn’t refer to the time when Jews forcibly converted other peoples or

carried off their women and forced them to submit to Jewish law and customs. He

sidestepped discussion about biblical founding fathers born to heathen

concubines. As far as Reverend Bronsky was concerned, the rule was that you

were Jewish if your mother was Jewish. Converts were accepted, but not actively

recruited.

However, he concluded firmly, converts cast off their previous existence when they

became Jewish, and once they were accepted into the Jewish community they

were to be regarded as Jewish like the rest of us.

This was a sophisticated argument for school children to grasp. We are the

Chosen People and therefore different to the rest of the world. We don’t really

want them to join Us, but if they knock on the gates convincingly and persistently

enough, We’ll let them in after they have passed stringent tests not required of Us,

and from then on they will be full members and everybody has to forget that they

once lived beyond the gates in the realm of The Others.

This is a question of faith, not logic, and you can’t expect a child to understand

that.

The issue of conversion to Judaism is not resolved by the rules. It is hard to

suppress the knowledge that somebody is a convert and act as if they are ‘really’

Jewish. As I lived my early social life largely among Jews, I have an instinctive

antenna for ‘Jewishness’, even in strangers — in the same way people from

similar ethnic backgrounds often identify each other in a wider society. I

sometimes felt this Jewishness about people I met in Eastern Europe, even before

the end of the communist era. Subsequently they actually discovered they were

Jews — their families had kept it hidden for decades. If I sense Jewishness

missing in somebody who calls themselves a Jew, the image of The Mouse

nibbles at a corner of my mind, raising the suspicion of conversion.

There can be no argument against the Jewish community’s definition of converts

as bona fide Jews. Every organised community sets its own entrance

requirements and membership tests. Yet if I had not been born Jewish, I certainly

wouldn’t knock at the gates of organised Jewry and ask to be taken in. People who

do so are operating on a religious basis that has little in common with my life or

perspectives as a Jew. My attitude to converts to Judaism is similar to how an

atheist regards converts to any organised religion.

From a sociological perspective, converts to Judaism are historical newcomers to

a group whose ethnicity has determined a particular fate over the centuries.

Converts come from families who have neither experienced the joy and pride, nor

suffered the pain and penalty of being Jewish through the ages.

The Mouse lay dormant for many years in her little dark hole in my subconscious

— until the signs of a growing conversion trend in Berlin’s Jewish community from

the early 2000s. At a conference of Jewish feminists in Berlin in 2003, I spotted

several versions of The Mouse clad in long-sleeved dresses despite the warm

spring weather, and adorned with religiously correct headwear, from a simple scarf

or beret to the colourful embroidered caps often worn by Middle Eastern men.

Some of the women in this attire were converts. My conference workshop on women artists’

expressions of Jewish themes was unforgettably dominated by a

German civil servant who explained at length how she had converted to Judaism

and asserted her new Jewish self by wearing a tallit, a prayer shawl, under the

jacket of her work uniform. (The shawls are traditionally for prayer, but Orthodox

men often wear them in daily life as well.) This was the first time I had encountered

a woman in street wear with a tallit, its knotted white fringes peeping out from

under the hem of her jacket.

That woman civil servant was no Mouse. She radically shook up my image of

Jewish converts. Breathing righteous fervour, she embarked on a lengthy account

of her struggle with the German bureaucracy to be allowed to wear religious garb

on duty, and her efforts to persuade her co-workers to accept her explicit

‘Jewishness’. The monologue concluded with effulgent praise for her husband,

who had not converted but had loyally supported her decision and her battle for

religious freedom in the workplace.

There is no difference between her arguments and those of Muslim women in

public service campaigning for the right to wear headscarves. It is an imposition of

private belief in the public domain, and has no place in a secular society. For most

acculturated Jews in Europe and America today, religious dress code is a non-

issue. They feel nothing in common with the ultra-religious sects and their ghetto-

throwback outfits of black hats and suits, beards and side locks. One of the

benefits of free religious practice in modern secular societies is that you don’t have

to be outwardly identifiable. If you choose to be, it may be a short step to a political

statement.

The misplaced fervour of religious converts has become a serious political issue

with the recruitment of people who become Muslims, join radical Islamist sects and

end up as fanatics and sometimes willing suicide bombers. As Judaism is not a

proselytising religion, discussion about the role of converts within the Jewish world

is less open. Jewish communities generally don’t publish statistics on conversion,

but it seems to be on the rise in Germany. In 2007 a well-known German Jewish

journalist, Henryk Broder, wrote a satirical article about Germans converting to

Judaism and then trying to tell all the others how to be good or better Jews. Broder

was particularly scathing about the fact that German converts do not share the

terrible history of the Shoah with the other members of the Jewish community. You

can’t take on centuries of suffering and persecution by proxy.

Around the same time as Broder’s article appeared, some long-standing members

of Berlin’s Jewish community were complaining sotto voce about the ‘convert

takeover’ of one of Berlin’s synagogues. The general opinion was that converts

should be seen but not heard. Meanwhile, more than a few converts, encouraged

by growing liberalism in other quarters of the community, took up studying for

rabbinical exams.

By the summer of 2007, Sonja, a Jewish friend whose family history in Berlin goes

back several generations, was complaining about a female convert who had

become a rabbi and was now criticising other Jews for not knowing the holy texts.

The new rabbi’s attitude smacks of Protestant bible fetishism. Strictures on

studying the scriptures, with their overtones of intellectual superiority, merely

alienate people who attend synagogue for its social side, to get away from the

daily grind and relax among friends within their community.

But if you’re not born into it, where does that sense of community come from? The

question is doubly important in Germany. Since the Shoah, there have been deep

divisions in society between victims and perpetrators, between people who

resisted and those who kept their heads down in the Nazi era. More than 60 years

later, the divisions are still there, transported by family histories that continue to

defy explanation, demand constant re-examination and inspire anger and sorrow.

A person who has grown up on the ‘other side’ can’t know what it’s like to light a

row of candles on Holocaust Memorial Day and watch them burn, often without

even knowing exactly how their murdered relatives died.

“When a converted German woman stands up as a rabbi to read from the list of

Shoah victims, how do we know it wasn’t her grandfather who murdered them?”

Sonja asks. There’s no answer. Born a generation after the war, the German

woman can’t be held responsible for her grandfather’s actions. Yet here in

Germany, conversion to Judaism inevitably raises the issue of blood, inherited

guilt and complicity. There is no rational answer because there is no rationality

possible in the face of the Shoah — or any other genocide. In the end, people

follow their feelings (and ingrown prejudices).

Hanging over all this is the big question mark of inherited guilt. Germans who

convert to Judaism often display the exaggerated philo-Semitism of descendants

atoning for the sins of their forefathers. Maybe they hope that if they chant the

prayers and blessings often enough and keep a kosher kitchen, they will be able to

expunge the collective or individual guilt with which history has burdened them.

This kind of thinking belongs to the general (predominantly Christian) perception of

atonement in western religious culture: it has much in common with penance,

charitable works and donating money to the poor.

However genuinely some German converts embrace their new Jewish faith, the

suspicion remains that they are trying to cast off a burdensome identity. You can

sense this in the fervour of new converts who broadcast each stage in the process

of their entry into Judaism. Some emergent Jews can talk inexhaustibly about the

theory and practice of the religion, the wit and wisdom of their rabbi, and the

salutary effects of daily prayer, honouring the Sabbath, and Torah study. I have

attended celebrations to mark the circumcisions of middle-aged male converts

where details of the Operation circulate in whispers while the happy celebrant,

dressed in his Saturday best, bathes in the aura of belonging to the Chosen

People at last.

.

.

It is not comfortable to be there for the purpose of giving somebody else the sense

of identity and community you haven’t found yourself. The phenomenon of

conversion in western societies may be interesting from a psychosocial viewpoint,

but I can hardly cheer on new recruits when The Mouse is peeking over my

shoulder — and I am pulled back to the teenage frustration of sitting in the dimly-lit

synagogue with my family on Saturday mornings and festivals, while beyond the

closed doors Sixties London is swinging in the bright sunshine of a summer of

love. The memory revives my teenage rejection of religion and the joyful, liberating

dive into anonymous apostasy and universal political causes. Harking back to the

critical spirit of those times, I wonder at today’s converts voluntarily jumping the

hurdles to join an anachronistic and largely patriarchal set-up whose current trend

is towards a split between ultra-religious orthodoxy and New Age adaptations. But

maybe I can’t understand converts to Judaism because they believe in God, and

not just any god, but the Jewish God.

Conversion takes us back to the mystery of religion, and why people believe. It

brings us slap up against the borderline between religion and atheism, spirituality

and rationalism, and right up to date with the atheist crusade that has occupied so

much media space since the mid-2000s. On a global scale, the issue of

conversion has gradually shifted from personal matters like contacts, convenience

and life phases to political issues of head-counting and fanaticism, splinter groups

and sects. In some parts of the world, the 20th century left a gaping hole in belief

systems and a mass of individual and collective identity problems, and religion is

being used as a way to fill the gap. In this process, the number of proselytes in

Judaism is minuscule compared with the conversions or changes of faith taking

place in other religions.

The days are gone when self-preservation or the desire for assimilation forced or

prompted Jews to convert to other religions. Since the Holocaust, it has been